Contrasting Saul and David. Creating comic books and stop-motion videos of the events. Memorizing Scripture. Becoming familiar with key passages. All these techniques help Elizabeth Jacobs teach the book of 1 Samuel at Trinity School of Durham and Chapel Hill in North Carolina. She loves coming up with creative lessons that make the Bible memorable.

While Elizabeth uses a variety of methods to lay the foundational content, she incorporates one consistent technique to close her units of study: seminar style discussion. The “what?” of each biblical text needs to culminate with a deep discussion of the “why?” and “so what?” And Elizabeth has found few techniques so effective in wrestling with big ideas as seminar discussion.

“We often underestimate students’ capacity to have a mature discussion on difficult topics, but time and again, I have been impressed with their ability to rise to the occasion,” Elizabeth said. “The formality of seminar creates a sense of ‘tension,’ making students alert and giving them a sense of responsibility for the discussion. It brings out the best in my students.”

Elizabeth has been honing seminar-style discussion since graduate school, when she was introduced to several varieties of seminar. We asked her to share with us six tips for an inner-outer circle discussion, which is the variety she uses most often.

1. Set up the Room (and Roles) in Advance

In contrast to casual discussion, seminar is a formal setting with special seating, special roles, and assessment. This setting creates a tone for serious and thoughtful discussion—something students need more than ever in an instant-message culture. Students will feel the formality when they first enter the classroom since seats will be specially arranged. But setting a serious tone begins when you first set expectations: Give students the date of the discussion over a week in advance, and explain that it will be a culmination of their learning. The students’ role will be to fully carry the conversation, and the teacher’s role will be to listen and take notes. Students will not raise hands or direct comments to you, because you are not a participant. This discussion will be theirs. Students feel the weight of this trust and responsibility!

2. Divide the Class into Two Groups

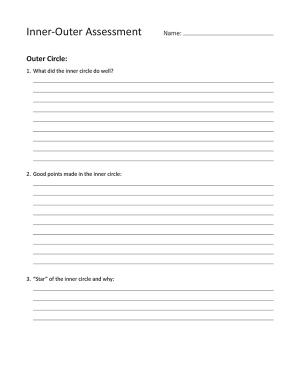

The Inner-Outer Circle model—also called “fishbowl”—keeps the discussion group small, thereby increasing each student’s participation. To implement, arrange chairs so that half the students are seated in the center in a tight circle, while the other half are seated around the perimeter, observing the inner circle. Distribute a handout for the outer circle to turn in afterward, explaining that they will share observations with the class. Ask: “What good points did participants make? What did they do well? What would you add?” This guide keeps the outer circle engaged in the important role of assessment and learning what makes for a good discussion.

3. Ask Open-Ended Questions

To sustain lengthy conversation, plan discussion questions that are “open-ended.” They should be complex enough that there are numerous correct responses that students can back with evidence. “What one word in the text is most important? Defend.” Or “What does the author want us to do as a result? Explain.” Open-ended does not mean that all answers are valid, since there are often many correct applications of Scripture—but also some wrong ones. Answers will be more or less correct, depending on how well students are analyzing and interpreting. Read more Open-Ended Questions in the resources we have provided.

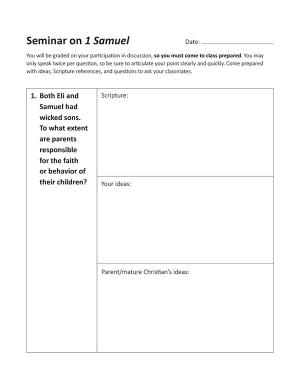

4. Provide Preparation Time

Elizabeth gives students her open-ended questions at least a week in advance, so they can consider their responses and cite specific Scripture verses (see included resources). To close their study of 1 Samuel, her questions revolved around themes found in the book: Israel wanting to be like other nations, godly parents sometimes raising ungodly children, and how students see influence-and-responsibility still today. The preparation time helps students piece together their ideas and walk in with more thoughtful application. Like Jennifer Baham, Elizabeth finds that interviewing a mature Christian adult is a highly beneficial step because it brings maturity into their thinking as they prepare. (And parents may thank you for the chance to have these conversations!)

5. Aim for Informed Spontaneity

The best discussions are a blend of preparation and spontaneity: Participants come in having done prior thinking, but they also listen and reply extemporaneously. Balancing these “opposites” can be a challenge! When students record ideas in advance, they may come with better content but then simply read off their sheet, without really listening and responding to each other. So, plan to set different goals from one discussion to another to balance preparation and spontaneity. Consider asking students to turn in their written notes before the discussion begins, so that they still receive credit for all their preparation but are free to focus on building the conversation authentically.

6. Teach Students to “Sharpen” One Another

When a student says something significantly incorrect, we as teachers may want to step in immediately. A better strategy is to coach students to interact with and question one another. Make a note of what was said, and wait to see if the next one to three students will reply. If no one replies, interject: “I’d like to go back to what said. Does anyone have a different understanding?” The more we coach students to refer to the text, the easier it will be to gently question one another. Teach students to ask each other: “What verses did you draw that from?” Their answer will either inform the group of verses they missed or make the student aware that they did not have textual basis for their answer.

Sit Back and Enjoy!

When students carry on serious dialogue, it becomes a joy for the teacher to hear their thoughts. We tire of giving students content, as we wonder how much they are “owning.” It’s a breath of fresh air to hear what they come up with on their own! The same point of application made by a peer rather than the teacher may also be received better. Students use relevant examples and slang that help other students relate to the Scripture. And since every discovery comes through active learning, the “a-ha’s” stick with students longer.

Elizabeth loves seminar discussion because of the way it revolves around big ideas. “It combines academic study with spiritual formation, which is a tension I always feel in Bible class. It is a core academic subject at our school with a final exam, but students also need time to explore their personal faith,” she said. “Seminar is what spiritual growth looks like—examining belief, listening, and wrestling with the fact that answers are not always simple.”

Written by Heidi Dean

Seminar is student-led. Teachers listen and take notes, choosing either to facilitate or to remain outside the circle.

Elizabeth’s class makes comics with an iPad app to lay foundational content.

Students on the outer periphery listen to the inner circle’s discussion.

Inner-Outer Assessment sheet

Blank “Inner-Outer Assessment” sheet

Open-Ended Questions sheet

Suggestions for open-ended questions to use in a classroom seminar discussion