Historically, scientists, farmers, environmentalists, birders, government agencies, and more have kept journals and records of seasonal changes, temperature, and other unique observations. Learning to observe and communicate findings are lifelong skills that are still practiced by people of all ages.

Teaching inquiry science from a Christian worldview allows students to engage in God’s creation and discover truths about order, intricacy, and community in his created world. Adding a component of journaling allows students to put a voice to those discoveries and reflect on the processes, structures, and wonder he set before us.

Susan Koppendrayer, STEM education specialist, met with CSESA lead teacher and grade one Abbotsford Christian School teacher Susan Dykshoorn to talk about the how she incorporates scientific observations and language arts skills into science journaling practices.

Benefits of Journaling

There are many benefits of teaching and using journaling practices in the science classroom. Journaling is especially helpful for the teacher in the self-contained elementary classroom.

Journaling helps:

- Students learn to put a voice to the processes they are engaging in and what they have discovered.

- Students learn basic English and language arts skills that are otherwise taught separately. When we use an inquiry approach to science, students need to ask questions, give reasons for their predictions, build their vocabulary, report accurate observations, and tie their discoveries and information together. These are all learning outcomes for both science and English/language arts. When we consider the cross curricular implications, it is a meaningful reflection to consider that is also the way God designed the world—creation is connected and interrelated!

- The writing process, which allows students to slow down their thought processes and reflect on what they are saying because of the time, energy, and fine-motor component of journaling, whether that takes place via pen and paper, computer document/form, or video presentation.

Susan Dykshoorn’s grade one class wondered why we get sticky when touching candy canes. The question led to an investigation. Students put candy canes in containers of different temperatures of water and made observations as they dissolved. Susan had students draw their observations, label their pictures, and write what they observed in a sentence. Students found it was easier to say an answer quickly in a discussion than to write down their observations. Allowing students to make observations using pictures instead of words helped the learning become more authentic. (See Figure 1)

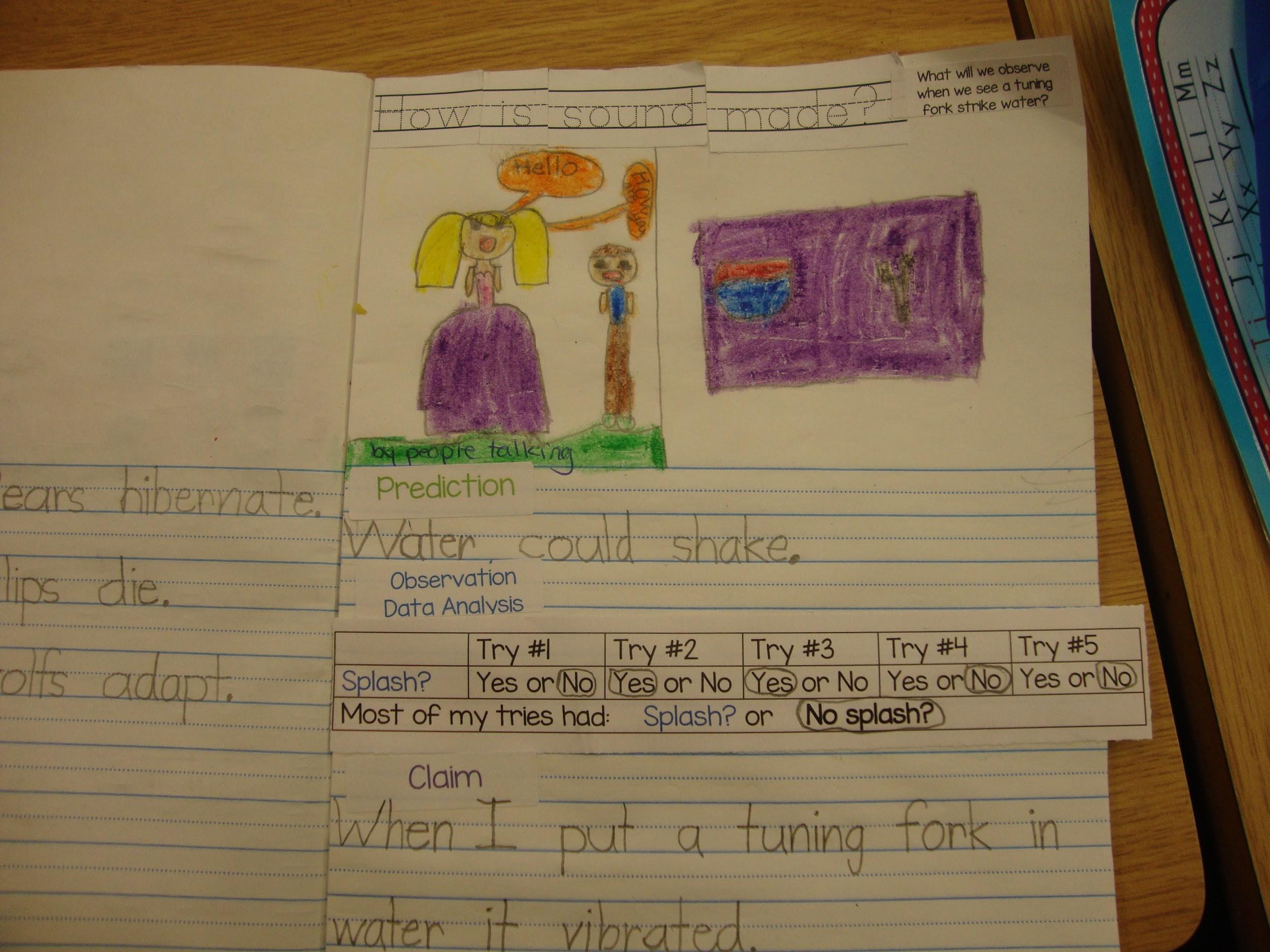

“I think one of the biggest challenges we face as teachers is to ‘fit it all in.’ How do we have time to teach everything the standards are requiring us to? Combining science and language arts through journaling is a way to teach more at once. It cultivates a classroom where students are growing as scientists and writers,” Susan said. In Susan’s classroom, students worked on tracing/copying print, drawing class answers, and correcting sentence structure—all while learning how to describe the scientific principles of sound. (See Figure 2)

Unstructured Journaling

Journaling is used to discover what kind of previous knowledge students have about a topic of study. Susan added, “Integrating writing in the scientific process provides natural scaffold opportunities and the chance for students to connect science with prior knowledge or past experiences.”

When planning an investigation about why candy canes make your fingers sticky, Susan first had her students write everything they knew about candy canes. This exercise built a sense of expertise and excitement going into the investigation but also gave the teacher the necessary information needed to understand a student’s prior knowledge.

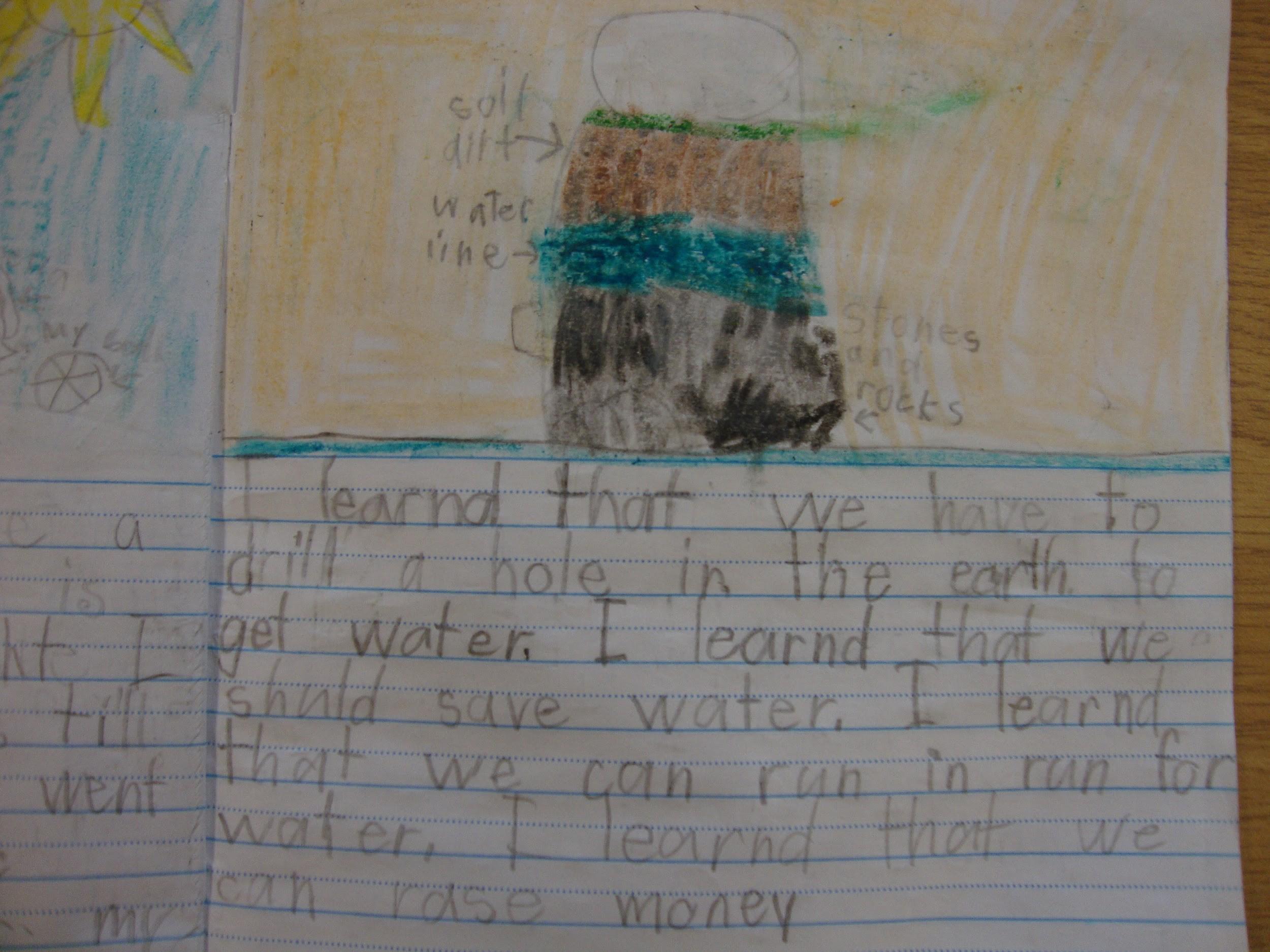

Unstructured Journaling provides a great opportunity for student reflection. In a water investigation, Susan’s first grade students looked at what organisms and elements existed in local water samples. Students also talked about areas of the world that do not have access to clean water. Journaling included reflections on how they felt, praises to God for the gift of water, practical actions they could take, and prayers for children who did not have access to clean water. (See Figure 3) “I often use journaling as prayer opportunities, where students can offer praise or concern to their Creator because of what they learned.”

Structured Journaling

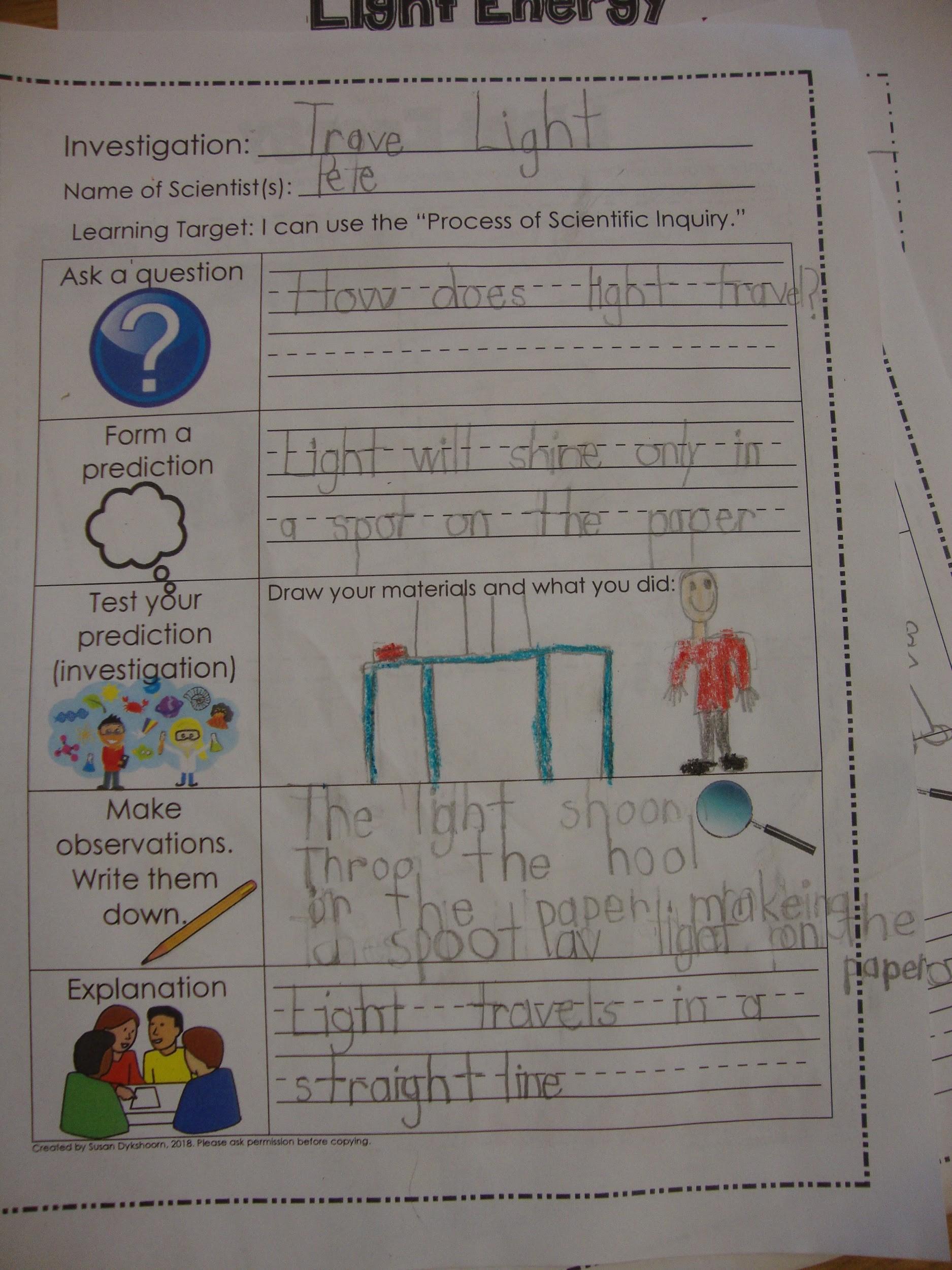

When engaging in a specific inquiry lesson or a STEM activity, Susan has her students fill in a structured journaling page. She generally starts with the question and carries on with the investigation. In the younger grades, she often gives them ruled lines to write on and leaves some parts for drawing pictures as a means of “writing.” The forms for upper elementary often include more space for writing as the investigations come to be more complex and detailed. (See Figure 4)

Visual Journaling

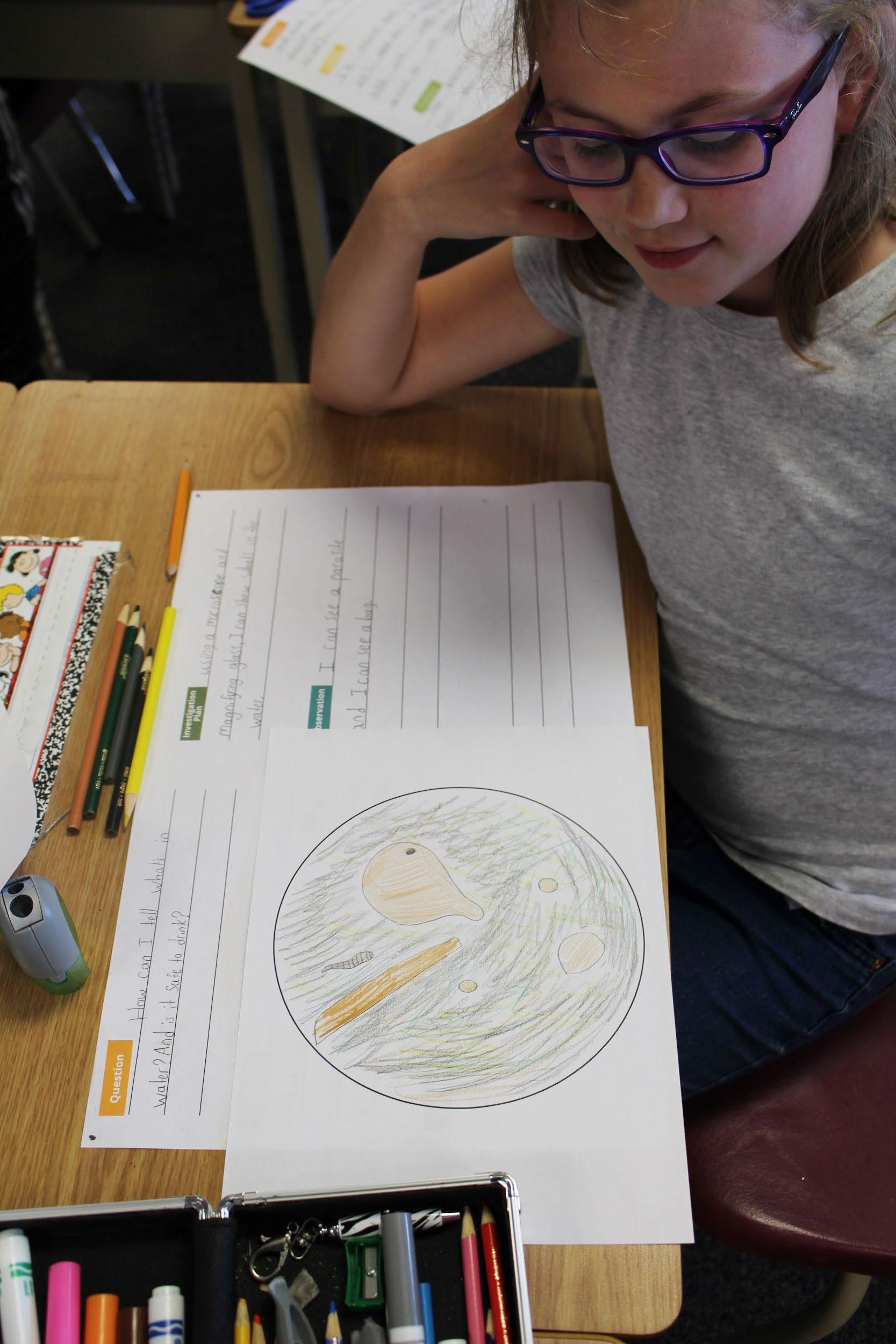

Not all journaling has to include long sentences and words. As science and English/language arts educators, we need to gauge what students can do and what will keep their motivation high. Often, teachers have students draw parts of the investigation rather than write it out. For visual journaling, one might have students draw and label the materials used. A “tape in” list of procedure steps and an observation table would be given to students by the teacher. Making observations in the form of sketches, photos, and mind maps help students to capture their point of view without having to find the right words to express what they see at that moment. Science journals from historic scientists like James Audubon, Lewis and Clark, and Jane Goodall all include visual journaling in the form of labeled sketches that capture the thoughts, observations, and sketches of what they saw. (See Figure 5)

Nature Journaling

Compared to journals in general, a nature journal creates an opportunity for the student to be an observer. As a teaching tool, the nature journal is easily used in all subjects and is easily adapted to all types of learning styles. Nature journals provide an opportunity for authentic learning, which incorporates drawing as well as writing. This type of journaling lends itself to reflection of God’s provision for his creation and our role as earthkeepers of all that he made. See the resource below from the Smithsonian, which will help teachers and parents get students started with creating their own nature journals.

Language Arts Science Connection

Science journaling helps students put observations and opinions into sentences and provides ways for teachers to incorporate cross-disciplinary language arts nonfiction and technical writing skills.

“I love how an investigation has fun, engaging and exciting parts, and adding the writing and language arts components built into it is a way for students to reflect and figure out what is going on in the world around them,” Susan shared.

Using Word Walls, science words of the week, and journal sentence starters provide opportunities for students to practice language arts skills and for teachers to pair literacy standards with science content.

Big Word of the Week: Each week introduces a new and challenging word to students. Talk about how to read it and teach phonetic rules as they apply to the word. Discuss the definition and find examples of where we might use this word or where this definition occurs in the world around us. Older grade levels can be challenged to take the word home, find the meaning on their own, and share it at school with the class to come up with a standard definition between classmates.

Word Wall: Word walls list the words students NEED to know at grade level. Adding vocabulary words learned in science investigations help to create a shared vocabulary and classroom conversational words.

Alphabet board: Brainstorming all the words related to the topic of the science investigation helps teachers see students’ personal knowledge. During the unit, students begin to link definitions to the list of words created throughout the investigation. Many teachers also add an alphabetical vocabulary section in science notebooks to helps students build a deeper understanding about the subject of study and inquiry science.

Sentence starters: Science starters such as I notice, I wonder, At first, I thought, I think . . . make it easier for students to organize their thoughts and organize their ideas. At the start of the year, teachers often have students write a list of possible sentence starters in the front of their science journals.

When reflecting on the use of journals in science, Susan said, “One of the biggest ‘aha’s I’ve learned in the process of integrating the inquiry model and language arts in the classroom is that you don’t have to do it ALL at once or teach it ALL at the same time.”

Incorporating journaling can be done at school and at home in all subject areas. This cross-curricular practice provides a way for students to demonstrate their understanding using words, diagrams, and sketches. Most of all, journaling allows students a chance to slow down and reflect on God's order and design in his creation.

Figure 1: Using pictures and words, helps student learning to be more authentic.

Figure 3: Unstructured journaling gives students the freedom to demonstrate their prior knowledge, unique perspective, and personal connections to faith and learning.

Figure 4: Structured journaling allows the student to demonstrate specific learning objectives.

Figure 5: Visual Journaling is an effective way for students to display their understanding and observations using sketches, color and diagrams.

Introduction to the Nature Journal

This free booklet from the Smithsonian provides historic and practical techniques for teachers and parents who want to start their own nature journal.